Professional dissonance: A promising concept for clinical social work.

By: Melissa Floyd-Pickard

Taylor, M. F. (2007). Professional dissonance: A promising concept for clinical social work.

Smith College Studies in Social Work, 77 (1), 89-100.

This is an Author's Original Manuscript of an article whose final and definitive form, the

Version of Record, has been published in Smith College Studies in Social Work [2007]

[copyright Taylor & Francis], available online at:

http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1300/J497v77n01_05.

Abstract:

Social workers in mental health face a complex climate where they encounter value-laden

intervention choices daily. Examples of these choices may include deciding to initiate treatment

in spite of a client's wishes to the contrary, making a decision to break confidentiality, feeling

pressured to diagnose a client with a reimbursable condition despite a treatment philosophy that

may be to the contrary, or feeling the need to “pick and choose” therapy topics in light of severe

shortages in benefit coverage. These and other scenarios put social work clinicians at risk for

professional dissonance or what has been called a feeling of discomfort arising from the conflict

between professional values and expected or required job tasks. The current article explores

professional dissonance as a pertinent concept for social work in general, and mental health

social work in particular. The theory base of the concept is explored as well as its utility for

understanding burn-out in a deeper way.

burn-out | value dilemmas | ethical dilemmas | ethics | existentialism | social work | Keywords:

clinical social work | mental health

Article:

PROFESSIONAL DISSONANCE DEFINED

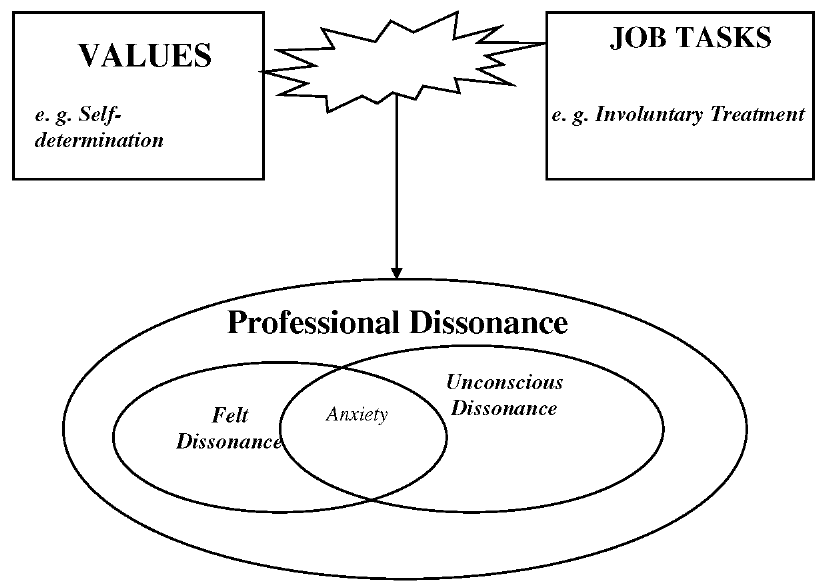

Professional dissonance is a new concept introduced here and is defined as a feeling of

discomfort arising from the conflict between professional values and job tasks. It has been

developed through the application of cognitive dissonance theory and existential theory to the

study of values and ethics and to the realities of practice climate in the mental health social work

arena. In this article, the author seeks to outline the philosophical background of professional

dissonance and its utility as a way of understanding the deeper dimensions of burn-out formental

health clinicians (see Figure 1).

In recent research findings (Taylor & Bentley, 2005), professional dissonance has been affirmed

as something seasoned mental health clinicians struggle with; however, the purpose of this article

is to explore the conceptual basis of professional dissonance. Accordingly, the research findings

will not be discussed in detail.

Social workers are regularly asked, and often required, to formulate practice decisions that both

protect society and maximize the rights of the individual–perhaps an impossible task. When the

two aims are incompatible, social workers find themselves in the position of making a practice

decision that may be unwanted and/or directly opposed by the consumer. An example of such a

decision would be requiring an actively psychotic but not currently dangerous consumer who is

handing out leaflets in the park to be hospitalized against his/her will. The decision to hospitalize

may conflict with the social worker’s value commitment to self-determination. In these and

many other situations, social workers have to deal with layers upon layers of competing values

(Loewenberg, Dolgoff, & Harrington, 2000). For example, they may have a personal

FIGURE 1. Schematic of Research Concepts

value about self-determination: “I believe in the importance of choice above all else”; a group

value: “I belong to X organization that opposes involuntary treatment”; a societal value: “I want

to feel safe when I take my kids to that park”; and a professional value: “Agency policy requires

me to intervene since I’m the case manager.” These value issues are further complicated by the

fact that the worker may encounter competing values on each one of the levels. For example, a

social worker, referring back to her/his professional values as exemplified in the NASW Code of

Ethics, encounters mixed direction: “I can intervene based on the NASW Code of Ethics, but the

Code also says I can restrict self-determination when it’s an imminent risk.” This exposition of

levels of values involved in daily social work decision making is but one example of the

potential complexity in intervention that faces mental health practitioners.

PHILOSOPHICAL BACKGROUND OF PROFESSIONAL DISSONANCE

The core ideas of existential theory have influenced psychology, literature, and sociology as well

as social work, and provide an important philosophical background in the conceptualization of

professional dissonance. Existential theory is important to professional dissonance because the

key existential issues of “authenticity” versus “bad faith,” and “ontological guilt” versus

“ontological anxiety,” speak to the current struggle in mental health practice to negotiate a social

work position that simultaneously protects a consumer’s rights (even to fail) and ensures the

practitioners’ ability to make professional, caring, and sometimes unpopular decisions about how

to intervene. Exploring the themes of existential philosophy also illuminates some reasons why

the perennial struggle inmental health, around what is right and what is wrong to do when

intervening in consumer’s lives, is so important. An existential philosophical background

additionally suggests why social workers need to feel good about the decisions they make and

what can happen when they do not.

Professional dissonance can accurately be classified as an existential problem in that it relates to

feelings which directly impact on our perception of ourselves as people, our feelings about the

kind of people and professionals we are, and our feelings about how we should live our lives and

fulfill our jobs. As Maddi (1996) points out, existential psychology, for all its diversity of

thought, emphasizes above all else the central tenets of being genuine, honest, and true, and of

“making decisions and shouldering responsibility for them” (p. 155). It is interesting to note that

these themes are the opposite characteristics of a state of depersonalization, a dimension of

unresolved burn-out (Pines & Maslach, 1978).

The dissonance and dissonance resolution processes are ones filled with confusion, angst and,

hopefully in the end, professional and personal growth. Pointing to a similar process, existential

philosophy affirms the opportunity for and necessity to form meaning out of suffering (Krill,

1996). Social work practice is filled with examples of consumers and families coming through

crises and illnesses with greater life understanding. Author and mental health consumer, Lori

Schiller (Schiller & Bennett, 1994) ends her biography as follows:

Looking over my life, I know now that I don’t want to go back. I want to go ahead . . . If

my life and my experiences can help other people find their ways out of darkness, I will

know that I have not wasted the great gift I have been given: the chance to begin life

again. (p. 270)

Similarly, when mental health practitioners confront feelings of angst, conflict, and frustration

before coming to the best practice decision they can, they are attempting to protect excellence in

practice.

While many aspects of existential theory have been helpful in developing the concept of

professional dissonance, the existential concepts of ontological guilt and ontological anxiety

have most influenced the conceptualization. In order to understand these ideas, the existential

concepts of being and being-in-the-world, authenticity, and bad faith are first presented and

briefly defined. An exposition of ontological guilt and ontological anxiety follows.

Being and Being-in-the-World. Existential philosophers place a great deal of emphasis on being.

Maddi (1996) points out that the German word for being (“daesin”) does not carry the static

connotation that “being” has in the English language. Instead, the word is more active and

actually means, “becoming.” In this way, the existential focus is on human potentiality. In order

to always be “becoming” and not have stagnated, the person must continue to act authentically

and avoid bad faith actions that delude and detract from the metamorphic process of becoming.

As it applies to mental health practitioners, the concept of being would, among other things,

connote continuing to develop as an excellent practitioner, working hard to lend individuality to

every practice situation, and having a dynamic, present orientation.

Authenticity versus Bad Faith Actions. Authenticity is often used as a synonym for genuineness.

Hepworth, Rooney, and Larsen (1997), in their widely used direct practice social work textbook,

define authenticity as “the sharing of self by relating in a natural, sincere, spontaneous, open and

genuine manner” (p. 120). They further describe the authentic social worker’s verbalizations as

congruent with their thoughts and feelings. In this way, they relate to consumers as real people,

expressing and taking responsibility for their feelings instead of denying them or blaming the

client for them. This focus on congruency between thoughts and feelings, and on assuming

responsibility for them whether or not they fit in with societal ideas of what is normal or good, is

closely related to the existential focus on authenticity. The existential hero, exemplified in texts

such as Camus’ (1946) The Stranger and Sartre’s (1947) The Age of Reason, embodies the ideal

of “authenticity” and is therefore often seen as abnormal or strange as s/he strives to realize

“being.” By acting in accordance with internal guidance, the existential hero avoids being

deluded by the trappings of normality and the conformity of society. In this way, bad faith

actions are guarded against and the individual continues her/his process of “becoming.”

Bad faith actions are the antithesis of authenticity. When an individual acts in a “bad faith” way,

s/he is acting against what his or her inner voice is directing. For example, a social worker who

internally supports an individual consumer’s stance not to take medication because the worker

believes that for this consumer the disadvantages outweigh the advantages, commits a bad faith

action when s/he pursues an inpatient commitment due to pressure from a supervisor or from the

consumer’s family. Similarly, a practitioner who upholds self-determination simply because s/he

doesn’t want to have to struggle with the paperwork involved in a commitment procedure, even

though the consumer needs to be hospitalized, commits a bad faith action as well. Individuals

who continually choose bad faith actions over authentic responses stop progressing as

“becoming” human beings. They may also stop taking responsibility (another key existential

concept) for their choices. In the examples above, the social workers may blame their choices on

society, on a difficult family, or even on the consumers themselves. But when the becoming

process halts, individuals become aware of feeling bad or being in psychological pain. According

to existential psychology, the individual feels bad due to the cumulative weight of ontological

guilt accumulated through repeated bad faith actions. Maddi (1996) suggests this is what Soren

Kierkegaard, one of the first existential philosophers, meant by the phrase “sickness unto death”

(p. 162), and what Thoreau was getting at when he said most people “lead lives of quiet

desperation” (p. 162).

Ontological Anxiety versus Ontological Guilt. In current research, dissonance is related to the

concept of anxiety, one that existential writers have long argued is misunderstood. Rollo May

(1983), a prominent existential author, wrote that the German word Freud and Kierkegaard,

among others, use for anxiety is “angst.” While it has no exact English equivalent, angst has

been translated as “dread” as well as “anxiety,” and captures the experience of being “torn,” or in

a dilemma. Accordingly, May points out that anxiety “always involves inner conflict” (p. 111).

Anxiety has a “becoming” quality in that it can lead to growth (Maddi, 1996). One has daily

choices either to continue becoming and face the resulting ontological anxiety, or to simply

choose comfort and stasis and therefore stagnate. Maddi describes ontological anxiety, or the

anxiety of becoming, quite eloquently:

Only when you have clearly seen the abyss and jumped into it with no assurance of

survival can you call yourself a human being. Then, if you survive, you shall be called a

hero, for you will have created your own life. (p. 162)

Quite simply, ontological anxiety is the price of living authentically. By contrast, choosing the

more comfortable, non-anxiety-provoking course of action will, in the short term, result in

feeling safer but in the long term lead to the more malignant state of “ontological guilt.”

Ontological anxiety, while uncomfortable, is more a pain of risk or a growing pain, while

ontological guilt is the pain of not accessing one’s potential, accompanied by the ache of regret

about “whatmight have been.” Series of bad faith actions result in heavy ontological guilt which

envelopes the individual in shame and regret, paralyzing their process of becoming.

One may well ask what all this abyss jumping has to do with intervention in mental health. But

existential psychology, with its focus on authenticity and responsibility, speaks directly to the

cost of bad faith actions (choosing not to jump). In this way, it answers the question of what

happens to social workers who consistently act in ways that conflict with their ideas about what

they should be doing, or as Margolin (1997) says, “who live in contradiction.” It also changes the

negative cast usually given to anxiety, and encompasses anxiety as a potential growing

experience. In this way, existential psychology balances the prevailing view of anxiety as burn-

out or pathological by casting it as a growing pain. The recasting is compatible with the concept

of professional dissonance, which combines the view of anxiety as problematic (as seen in

cognitive psychology and ego psychology) with the idea of anxiety as a possible vehicle toward

practice excellence.

PROFESSIONAL DISSONANCE AND BURN-OUT

Burn-Out, the “syndrome of physical and emotional exhaustion, involving the development of

negative self-concept, negative job attitudes, and a loss of concern and feeling for clients” (Pines

& Maslach, 1978, p. 224), has been called an occupational hazard for human service providers

(Gomez &Michaelis, 1995). Additionally, social workers in mental health are more likely to

experience burn-out and have decreased job satisfaction as comparedwith social workers in other

areas (Acker,1999). The three-dimensional construct of burn-out includes emotional exhaustion,

depersonalization, and feelings of reduced personal accomplishment (Enzmann, Schaufeli,

Janssen, & Roseman, 1998). As a concept, professional dissonance seeks to add a new element

to the discussion around burn-out and job satisfaction by exploring the ways social workers feel

torn or ambivalent about the ways their values and work interventions coexist. For example, a

practitioner may have worked tirelessly to help a consumer attain disability benefits that the

practitioner feels are desperately needed. The consumer, upon getting the hard-won benefits,

may decide that s/he really should work, despite not having been able to keep a job for more than

a few weeks in the past. In this example, the client’s wishes and right to self-determine must be

weighed against the practitioner’s view of the situation in making a decision about how to

intervene. In short, professional dissonance relates to the burn-out literature in that it attempts to

understand the inner lives of social workers and how their inner thoughts and outer actions may

contribute to burn-out.

PROFESSIONAL DISSONANCE AND COGNITIVE DISSONANCE THEORY

The theory of professional dissonance was conceptualized by Leon Festinger and other cognitive

theorists. Festinger (1962) developed cognitive dissonance theory in the 1960s as a “consistency

theory,” so designated because it emphasizes the premise that humans desire congruence in their

thinking and will act to reduce inconsistency among thoughts, and between thoughts and

behaviors. He defines cognitive dissonance as “the existence of nonfitting relations among

cognitions” (p. 3). In other words, a person who has two cognitions that are inconsistent,

experiences dissonance–a negative drive state similar to hunger or thirst (Aronson, 1997).

Festinger goes on to describe the reduction of dissonance as a basic process among humans.

More recently, Aronson (1997) expanded Festinger’s more “cerebral” brand of cognitive

dissonance by emphasizing the role behavior plays in causing dissonance. Aronson

conceptualizes dissonance as strongest when a cognition related to self-concept conflicts with a

cognition about behavior. In other words, dissonance is strong when an action contradicts a

belief about the self. This type of cognitive dissonance–the conflict between behavior and self-

concept–is seen as giving rise to professional dissonance. As it applies to social workers,

professional dissonance can occur when an individual’s identification with her/his professional

values conflicts with certain expected or required job tasks.

The issue of insight or perception in the conceptualization of professional dissonance is very

important. A social worker who has experienced and successfully resolved her/his dissonance,

whether positively or negatively, may not be aware of the process s/he went through to come

through the dissonant situation. On the other hand, another social worker may be very aware of

the parts of her/his job situation that create discomfort by placing her/him in a value-dissonant

position. For this reason, the dimension of felt value/job conflict is important in understanding

professional dissonance. It joins the other dimensions, unconscious dissonance and felt anxiety,

in framing the experience of professional dissonance (see Figure 1). It is simply defined as the

actual, felt, or reported discrepancy between a job intervention, such as placing a consumer in the

hospital against her/his wishes, and a professional value such as self-determination.

Festinger (1962) outlines three types of relationships among cognitions: irrelevance, consonance,

and dissonance. In an irrelevant relationship, the two cognitions have no relationship (“That

consumer is creative and energetic,” “I’m out of Post-It notes”). When cognitions are consonant,

the cognitions are consistent and complement one another (“That consumer is creative and

energetic,” “I really like that consumer”). In the final relationship, the two cognitions conflict

with one another (“That consumer is creative and energetic,” “The consumer is becoming manic

and needs to be hospitalized”). Dissonant cognitions result in discomfort accompanied by a

desire to make the cognitions more consonant, and thereby alleviate the discomfort (“It’s ok to

be high energy but she’s going too far,” “If I don’t act now she may get worse”).

In understanding the way professional dissonance applies to clinical practice, it is important to

explore how clinicians employ dissonance resolution strategies in attempting to alleviate their

discomfort (“I’m acting in her best interests, that’s my job,” “She’s been hospitalized a lot, one

more time is not going to make that much of an impact”). In this example, the social worker who

feels dissonant about having to hospitalize her/his “favorite” consumer, first attempts to

rationalize the intervention and then minimizes the impact of the intervention on the consumer.

The goal is to alleviate the social worker’s dissonance. In summarizing cognitive dissonance as a

theory, Harmon-Jones and Mills (1999) cite four ways in which dissonance can be reduced: (1)

by removing the dissonant cognition: “I had no choice”; (2) by adding new consonant cognitions:

“I’m helping her”; (3) by reducing the importance of dissonant cognitions: “She really doesn’t

mind being in the hospital”; and, (4) by increasing the importance of consonant cognitions: “Her

safety is the most important thing.” This last strategy mirrors the process of ranking values by

importance in individual situations that Loewenberg, Dolgoff, and Harrington (2000) have

described.

An individual clinician’s insight into his or her own dissonance reduction processes may wax

and wane, in much the way a person may unconsciously use a defense to manage anxiety without

being aware of what s/he is doing. Even if the person is aware, once experienced dissonance has

been reduced or resolved, s/he is comfortable again and has a stake in remaining comfortable

instead of rehashing the reasons for the initial dissonance. This is important in understanding

professional dissonance as a supervisory issue, because the clinical supervisor’s role may be to

stimulate dissonant discussions that raise anxiety in an effort to illuminate constructive

dissonance reduction. This again underlines existential theory’s emphasis on anxiety as growing

pains, versus society’s current stance that anxiety is pathological.

PROFESSIONAL DISSONANCE’S IMPORTANCE TO SOCIAL WORK PRACTICE

The concept of professional dissonance is significant to clinical social work practice for several

reasons. First, it draws attention to the phenomena as it affects clinical social work theory and

practice, and underlines the need for future inquiry into practice-based issues in mental health.

Second, it illuminates the complexities and ramifications of social work practice decision making

in cases that present value collisions (Frankl, 1988). In this way, it makes social work values,

particularly the value of self-determination, an area of future inquiry, and an essential topic for

practice-based research. Finally, the study of professional dissonance has implications for

practitioners’ relationships with consumers in mental health practice, and for the makers of

mental health policy.

Conceptualizing professional dissonance adds another dimension to research about burn-out and

the protection of job satisfaction. The ways in which social workers operationalize social work

values and use them to guide their practice needs to be studied further (Rothman, Smith,

Nakashima, Paterson, &Mustin, 1996) as does the way practitioners rank order values by

importance, depending on practice situations (Loewenberg, Dolgoff, & Harrington, 2000).

Creative, effective strategies for supporting practitioners in negotiating difficult practice

decisions need to be prioritized in order to insure longevity, despite contradictions in mission and

values and actual practice life (Margolin, 1997). Professional dissonance emphasizes the

imperative nature of research that aims to support practitioners in the decisions they make around

practice interventions with mental health consumers.

Social work in today’s practice environments is complex. Accordingly, it is essential that the

profession support an ongoing dialog and facilitate an engaging climate in which

multidimensional issues that lend clarity to value dilemmas in practice can be explored. Social

work values need to be concretized for daily practice, so they take on real-life meaning and

benefit both consumers and social workers. Focusing attention on values and value conflicts

protects the mission of social work and vitalizes the Code of Ethics with living examples of its

value and domain in daily clinical practice. Consistent support and protection of career

satisfaction ensures individual social worker’s longevity in the profession, improves consumers’

quality of life, and facilitates excellence in the profession’s continued partnership with persons

who have mental illness.

Social workers need to feel safe in their organizations if they are to continually analyze ongoing

practice decisions. Professional dissonance need not have negative effects if room is made in

professional organizations and in agencies for ongoing dialogue and value clarification. In this

way, the existential focus on anxiety as a possible vehicle for growth is applied to experiences of

professional dissonance in day-to-day practice. By supporting social workers in deliberating

about practice issues, we foster a healthy tension that may well lead to more innovative practice

and policy interventions.

REFERENCES

Acker, G. M. (1999). The impact of clients’ mental illness on social workers’ job satisfaction and

burnout. Health and Social Work, 24(2), 112-120.

Aronson, E. (1997). A theory of cognitive dissonance. American Journal of Psychology, 110(1),

127-137.

Camus, A. (1946). The stranger. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Enzmann, D., Schaufeli, W. B., Janssen, P., & Rozeman, A. (1998). Dimensionality and validity

of the Burnout Measure. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 71(4), 331-33.

Festinger, L. (1962). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Frankl,V. E. (1988). The will to meaning: Foundations and applications of Logotherapy

(Expanded edition). New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Gomez, J. S. & Michaelis, R. C. (1995) An assessment of burnout in human service providers.

The Journal of Rehabilitation, 61(1), 23-27.

Harmon-Jones, E. & Mills, J. (1999). An introduction to cognitive dissonance theory and an

overview of current perspectives on the theory. In E. Harmon-Jones & J. Mills (Eds.), Cognitive

dissonance: Progress on a pivotal theory in social psychology (pp. 3-24). Washington, DC:

American Psychological Association.

Hepworth, D. H., Rooney, R. H., & Larsen, J. (1997). Direct social work practice (5

th

edition).

California: Brooks/Cole.

Krill, D. F. (1996). Existential social work. In Francis J. Turner (Ed.), Social work treatment (pp.

250-281). New York, NY: The Free Press.

Loewenberg, F. M., Dolgoff, R., & Harrington (2000). Ethical decisions for social work practice

(6th ed.). Itasca, IL: F. E. Peacock.

Maddi, S. R. (1996). Personality theories: A comparative analysis (6th edition). Brooks/Cole

Publishing.

Margolin, L. (1997) Under the cover of kindness: The invention of social work. Charlottesville,

VA: The University Press of Virginia.

May, R. (1983). The discovery of being. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

Pines, A. & Maslach, C. (1978). Characteristics of staff burnout in mental health settings.

Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 29, 223-233.

Rothman, J., Smith, W., Nakashima, J., Paterson, M., & Mustin, J. (1996). Client self

determination and professional intervention: striking a balance. Social Work, 41, 396-405.

Sartre, J. (1947). The age of reason. New York, NY: Albert Knopf.

Schiller, L. & Bennett, A. (1994). The quiet room: A journey out of the torment of madness.

New York, NY: Warner Books.

Taylor, M. F. & Bentley, K. J. (2005). Professional dissonance: Colliding values and job tasks in

mental health practice. Community Mental Health Journal, 41(4), 469-480.